Have you ever sat down and wondered to yourself, “How does a hydraulic press work?” We actually think about it all the time here at Atlantic Hydraulic Systems.

The fundamentals of a hydraulic press were actually made possible because of a French philosopher named Blaise Pascal. In fact, Pascal theorized and developed what we now know as Pascal’s Law.

In this article, we’ll delve into Pascal’s Law, the mechanics of hydraulic presses, exploring the force exerted, pressure applied, and the fascinating principles that make them tick.

What Is Pascal’s Law?

A change in pressure at any point in an enclosed incompressible fluid at rest is transmitted equally and undiminished to all points in all directions throughout the fluid and acts at a right angle to the enclosing walls.

How Does A Hydraulic Press Work?

Hydraulic presses harness the hydraulic principle, a concept grounded in Pascal’s Law, to perform various tasks. This hydraulic principle dictates that any pressure applied to an incompressible fluid within an enclosed system will be transmitted uniformly in all directions.

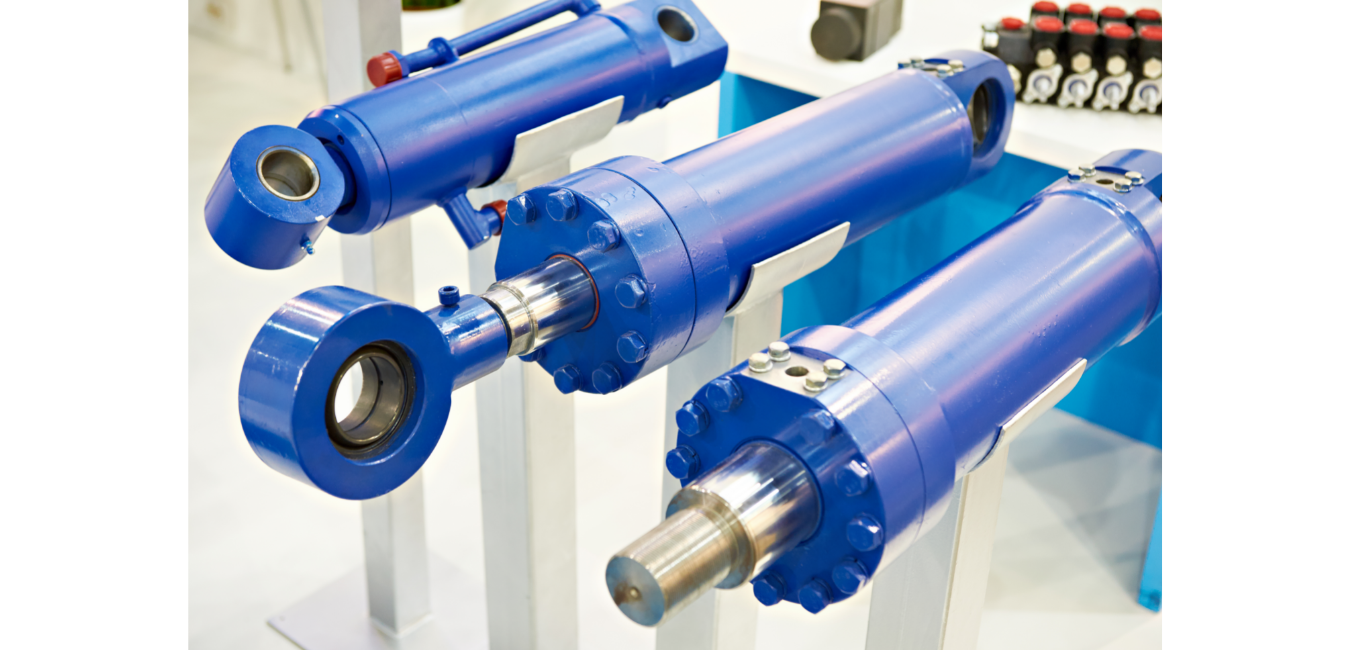

In a hydraulic press, there are two interconnected cylinders: a larger cylinder and a smaller cylinder. High-pressure hydraulic oil is supplied to the larger cylinder, creating an increase in pressure. As per Pascal’s Law, this increase in pressure is transmitted undiminished throughout the fluid. Consequently, it exerts a substantial amount of force on the piston within the larger cylinder.

This force is then leveraged to extend the larger cylinder, which in turn exerts pressure on the object being pressed. The mechanical force applied to the smaller cylinder is multiplied many times over, resulting in a force exerted on the object that is significantly greater than the initial force applied to the hydraulic system.

Check Out Our Collection Of Hydraulic Power Units!

This process is a direct application of Pascal’s Law. The law states that the pressure applied to any part of the enclosed liquid will be transmitted equally in all directions through the liquid.

You may have already seen the damaging effects of a hydraulic press on everyday household items in YouTube videos. Still, a hydraulic press is even strong enough to flatten a solid natural diamond in an instant!

Why Use Hydraulic Presses?

The application of hydraulic systems in presses includes various benefits, making them a preferred choice over mechanical alternatives:

- Cost-Effective: Hydraulic presses are a cost-effective solution for a wide range of tasks.

- Durability: They are known for their durability and minimal breakdowns.

- Precise Control: Hydraulic systems offer precise control over the amount of force exerted and the speed of operation.

- Noise Reduction: Hydraulic presses operate more quietly than their mechanical counterparts.

- Power Amplification: These systems can efficiently convert a small input of power into a substantial force output, illustrating the power of Pascal’s Law.

In addition to their use in presses, hydraulic systems find applications in various fields, including hydraulic brakes and numerous industrial processes. The capacity to harness the hydraulic principle and Pascal’s Law in hydraulic presses demonstrates the remarkable efficiency of incompressible fluids in transmitting force and pressure.

Understanding how a hydraulic press works involves appreciating the fundamental hydraulic principle governed by Pascal’s Law. This principle allows hydraulic systems to magnify mechanical force many times over, making them indispensable in various industries and applications.

You’ll find our experts happy to answer any questions you have about hydraulic fluids and presses!

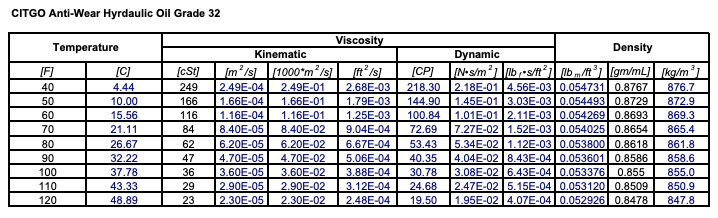

An example of a chart that shows the hydraulic oils’ viscosity range

An example of a chart that shows the hydraulic oils’ viscosity range